Bhagavad-Gita, by all accounts, is rather an unusual text.

Bhagavad-Gita, is revered as one among the exalted triad of the fundamental philosophical texts (Prasthana-traya) of the Sanatana Dharma; the other two being the principal Upanishads (Upadesha prasthana, Śruti-prasthāna) and the Brahma Sutra (Sutra-prasthana or Nyaya-prasthana) , which is the condensed essence of Upanishads . The Gita is accorded the position of Sadhana-Prasthana (practical text); and, is regarded as the starting point of remembered tradition the Smriti-Prasthāna.

[Sruti is the directly perceived truth, hence more authoritative. Smriti is the heard or meditated upon tradition that follows the Sruti.]

: – And yet; the Bhagavad-Gita is located within the Mahabharata, an Epic which is classified as Ithihasa, a narration of the past events. The Gita is conceived and developed as a solution to the climax of a Dharmic dilemma that emerges during the course of the Epic. As Van Buitenen said; it was not an independent text that somehow wandered into the epic.

Mahabharata as Ithihasa is classified as Smriti, while the Bhagavad-Gita embedded within it is assigned a superior and an exclusive position of a Sruti, though it deviates, in some respects, from the traditional Sruti format.

[However, the famous philosopher Dr. Surendranath Dasgupta in his monumental History of Indian philosophy makes an interesting observation. In the Rig Veda, he observes, Vishnu is called as Gopa, Sipivishta, Urukrama, etc., but not as Narayana. Then he goes on to say, similarly, Bhagavad Gita does not use the term Narayana; but, the Mahabharata identifies Narayana with Vishnu. This, according to him, could show that Bhagavad Gita was composed much before Mahabharata tale was reduced to writing. He opines, Bhagavad Gita was composed at a time when Narayana was yet to be equated with Vishnu.

In contrast to that, Eknath Easwaran asserts that the Gita was composed much later under the realities of a new age. It ‘is not an integral part of the Mahabharata. It is essentially an Upanishad, and my conjecture is that it was set down by an inspired seer and inserted into the epic (later).’]

:– Regarding the plausible ‘Date’ of the Bhagavad-Gita , Justice Kashinath Triambak Telang, in his introduction to Bhagavad-Gita (Oxford, New Clarendon Press, 1875/ 1882) , conducts a detailed discussion covering various aspects , such as ; the language; the philosophical outlook; its treatment of the Vedas ; and its proximity to the Upanishad-like-ideas etc.

The language of the Gita differs from that of the Sanskrit of the classical age. Its style is naturally simple, direct and uncomplicated;. It is neither too terse like the Sutras; nor is it heavily adorned with the tropes (Alamkaras); and yet, it is not devoid of aesthetic appeal and beauty.

Further, its attitude to the Vedas is very interesting. It does hold the Vedas in high esteem. But, it says that one who has acquired certain level of devotion and exerts himself for further progress , rises above the Vedas (Gita-Ch.6-verse 44). The Upanishads also put forth similar views rejecting the validity of the rituals.

पूर्वाभ्यासेन तेनैव ह्रियते ह्यवशोऽपि स: । जिज्ञासुरपि योगस्य शब्दब्रह्मातिवर्तते ॥ ४४ ॥

pūrvābhyāsena tenaiva/ hriyate hy avaśo ’pi saḥ/ jijñāsur api yogasya/ śabda-brahmātivartate

Most of the references to the Vedas in the Gita pertain to its connection with the rituals (Karma-kanda). This is similar to the approach adopted by the Upanishads towards the Vedas. Further, some stanzas in the Gita resemble some in the Upanishads.

Further, the Gita (Ch.9, verse 17) refers to only three of the Vedas (Trayi)- Rig, Saman and Yajus; but, not to the Atharvana Veda.

पिताहमस्य जगतो माता धाता पितामह: । वेद्यं पवित्रम् ॐकार ऋक् साम यजुरेव च ॥ १७ ॥

pitāham asya jagato /mātā dhātā pitāmahaḥ/vedyaṁ pavitram oṁ-kāra/ ṛk sāma yajur eva ca

Another interesting point is that which relates to the castes and their divisions. The Gita states that such divisions are based in the differences in the qualities (Guna) and duties (Karma); and, that the various duties are performed according to the difference in ones qualities. The Gita does not equate caste with ones birth or heredity. This is markedly distinct from the prescriptions of the later Dharma-shastras like that of the Apastamba.

The view of the Gita appears to represent the practice that was prevalent in an earlier age, before the time of the Sutras of Apastamba (prior to Third Century BCE).

The Gita does not anywhere proclaim the superiority of the Brahmans. (Ch.10). The holy Brahmans and the Royal Sages (Raja-Rishi) are bracketed together, as a class. And, the Kshatriyas, in particular, are said be to the links between the Deities and the mankind. They are declared as being the highest among men (Narottama).This is very close to the happenings in the Upanishads

All these again point out that Gita is definitely prior to the Age of the classical literature; and, might be nearer or contemporary to the Age of the Upanishads or of the Aranyakas.

Justice Telang concludes: the various and independent lines of investigation, which we have pursued, converge to the point, that the Gita , on numerous and essential topics , ranges itself as a member of the Upanishad group, so to say, in Sanskrit literature. Its philosophy; its mode of treating its subject; its style; its language; its versification; and, its opinions on assorted subjects of the highest importance; all point towards that one conclusion.

The latest date at which the Gita can have been composed must be earlier than the Third Century BCE; though how much earlier to that cannot be stated precisely.

*

: – Though Bhagavad-Gita appears as a part of the Mahabharata, it is studied and commented upon as an independent text, complete in itself. All the Acharyas who wrote Bhashya-s (commentary) on the Gita regarded it as a Sruti; and a source text of valid knowledge. It was even considered as the fifth Veda (Panchama Veda); and, cited as a Pramana (a text of undisputed authority) on a range of questions.

: – The conversation (Samvada) that takes place in the Gita is not very lengthy, not exceeding 700 verses; and yet, it caused thousands of commentaries over the centuries.

[ The Bhishma Parva (the Sixth Parva in Mahabharata) is spread over 124 Adhyayas (chapters), in 4 sub (upa) Parvas (sections) ; and, having in all 5,381 shlokas (verses). Within that massive Parva, the Bhagavad-gita is just about 700 shlokas, contained in 18 Adhyayas (starting from the 25th and ending after 42nd chapter of the Bhishma Parva), which appear under the third Sub-Prava (Bhagavat-Gita Parva). Thus, Bhagavad-gita forms a very small portion of the Bhishma Parva; but, its value and significance is immensely huge – ‘A little shrine within a vast temple’.]

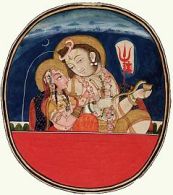

:- Gita regards the Absolute Reality as Brahman to which nothing can be attributed ; as well as Saguna Brahman , a divinity with most adorable qualities; and, also as an ideal human being in the form of Krishna, the manifest Brahman. Gita refers to all the three forms without contradictions. They all are viewed as the different aspects of the One or THAT which is beyond –Tat Param

[Gita does not mention the term Avatar at all. Perhaps the concept of Avatar was then yet to be evolved. But, the seeds of an idea of a God who descends and takes forms on earth are present- sambhavami yuge-yuge.]

: – As a philosophical text, Bhagavad-Gita is a part of the basic source-book of the Vedanta which speaks in terms of Brahman, the Absolute, infinite and eternal. But as a religious Book, it could even be reckoned as a Vaishnava text, since it regards Vishnu (Krishna) as the Supreme Lord of the Universe. And, it is closely associated with the Srimad-Bhagavata and related traditions of Vaishnava doctrine. Thus, Bhagavad-Gita is not only the revelation by Krishna, but also the revelation of Krishna as the Supreme Being.

[However , the scholars of the Kashmir Shaiva School, such as Rajanak Ramkanth (Sarvatobhadra – 850 AD); Bhatta Bhaskara (Bhagavad-Gita Tika – 900 AD); and, Abhinavgupta (Bhagavadgitarth Samgraha – 950 to 1050AD) interpreted Bhagavad-Gita from the Shaiva point of view and regard it as the one among the Shaiva-Agama class of texts.]

: – At another level, the Gita could even be seen as a personal god in conversation with a human being. The involvement of a divine being (as an inspiring leader) on an earthly battlefield and asking the warrior to carry on the fight is truly interesting. It, somehow, seems to mark the limits of the human; and , to point to the nature of war, prompted by god, as an avoidable necessity for restoration of moral order (Dharma) on the earth.

This view, needless to say, is highly debatable.

[The Samkhya concept of the Purusha and Parakrti; the passive and the active; the inspirer and the doer, runs throughout the Indian texts in one form or the other. The Nara-Narayana is the classic model of this concept. Here too, Krishna (Narayana) does not fight; but, motivates Arjuna (Nara) the warrior to carry on the fight. Krishna is the awakener (the Sun).]

:- The religion , which for whatever reasons is now known as ‘Hinduism’ , does not have a Book per se; but , therein , the Gita has come to be recognized as a Holy Book upon which one swears to ’tell the truth , the whole truth and nothing but truth’.

: – Further, while the other ancient Indian texts are gradually fading out of the discussions among the common people, the Bhagavad-Gita and its ‘message’ is still being debated, with some fervor . And, no other Sanskrit work approaches the Bhagavad-Gita in the influence it has exerted in the West as the chief philosophical statement of Hinduism.

: – The narrative structure of the Gita is rather peculiar, as the scholar Devdutt Pattanaik points out in his My Gita:

We never actually hear what Krishna told Arjuna. We simply overhear what Sanjaya transmitted faithfully to the blind king Dhritarashtra in the comforts of the palace, having witnessed all that occurred on the distant battlefield, thanks to his telepathic sight.

We never actually hear what Krishna told Arjuna. We simply overhear what Sanjaya transmitted faithfully to the blind king Dhritarashtra in the comforts of the palace, having witnessed all that occurred on the distant battlefield, thanks to his telepathic sight.

The Gita we overhear is essentially that which is narrated by a man with no authority but with a distant sight (Sanjaya) to a man with no sight but with full authority (Dhritarashtra). This peculiar structure of the narrative draws attention to the vast gap between what is told and what is heard.

Krishna and Sanjaya may speak exactly the same words, but while Krishna knows what he is talking about, Sanjaya does not. Krishna is the source, while Sanjaya is merely a transmitter.

Likewise, what Sanjaya hears is different from what Arjuna hears and what Dhritarashtra hears.

Sanjaya hears the words, but does not bother with the meaning. Arjuna is a seeker; and so , he de-codes what he hears in order to find a solution to his problem. Arjuna, during the ‘conversation’, asks many questions and clarifications’, to ensure that he properly understands the purport of the ‘discourse’.

In contrast, Dhritarashtra remains silent throughout. In fact, Dhritarashtra is not interested in what Krishna has to say; but, is rather fearful of what Krishna might do to his children, the Kauravas.

: – As regards the treatment of its subjects, the Bhagavad-Gita describes itself as the essence of all the Upanishads. The Upanishads by their very nature are philosophical speculations transcending the physical world. The Gita ,on the other hand , teaches about living a worthwhile, meaningful life in the world among fellow beings – Jivana- Dharma – Yoga.

:- Further, the Upanishads which aspire to understand the essential nature of all things in the Universe and in the individual, as also the relation between the two , emphasize the superiority of knowledge (Jnana) over action (karma).

In the Gita, Krishna , on the other hand, asks Arjuna to follow the path of action and to act decisively.

The confused Arjuna, helplessly, queries Krishna for a clear direction: ’Oh, Janardhana, if you consider Knowledge (Jnana) to be superior to action, why then do you instruct me to perform this terrible act?- janārdana tat kiṃ karmaṇi ghore māṃ niyojayasi keśava’ – (BG. 3. 1 – 2).

The Gita does not seem to favor renunciation or total withdrawal from the world resulting in inactivity, nivritti. Instead the Gita teaches the sort of Jnana that endorses renunciation of desires, of fruits of action. It advocates activity pravritti with the renunciation of the fruits of action. Gita terms it as ‘inaction in action and action in inaction’ akarmaṇi ca karma … karmaṇy akarma (4.18). That is, performing acts according to ones calling, with equanimity; and, relinquishing attachment to the fruits of one’s actions.

anaashrita karma phalam kaaryam karma karoti yah / sa sannyaasi ca yogi ca na niragnir na ca akriyaha

One who does not depend on the fruits of action but does the work which is his duty. He is a sanyaasi and also a yogi, not the one who has renounced fire (rituals) and not one who (merely) does nothing (Bg. 6.1)

yoga yukto vishuddhaatmaa vijitaatmaa jitenriyaha/ sarva bhutaatma bhutaatmaa kurvan api na lipyate

He who by following Yoga, has purified the mind; has controlled the mind; has controlled the senses; sees his own Self in all beings; and, does not get tainted even if he does work (Bg. 5.7)

[Krishna, of course, succeeds in reconciling the deep chasm between the two paths or approaches (Jnana and karma) by introducing the unique concept of internal renunciation, as opposed to external renunciation.

By reconciling otherwise two contradictory ideas, Krishna offers a realistic system which intertwines performance of one’s responsibilities in life without getting too attached to it. It cautions that an un-restrained desire for the fruits of one’s action, more often than not, leads to major blunders in decision making, both in personal and social life.

In this way, the Bhagavad-Gita adheres to both the ideals. It supports involvement in the performance of one’s social and moral responsibilities according to ones Dharma in life; and, at the same time it endorses the Upanishad ideal of self-realization which leads to liberation from confines of relative existence. ]

Manifold paths

The Gita begins with a response to Arjuna entering a state of despondency just at the time when he was required to perform. This is the initial problem of the Gita. Krishna’s teaching will, in later stages, cover several other paths or approaches to life; but, the initial focus is on the problem of action, with Karma Yoga as the solution. It is self-less performance with equanimity; equal acceptance of pleasure and pain; and, renouncing fruits of one’s action.

*

The Gita suggests that though we all are one in spirit, each one is different in her/his intellectual and psychological makeup; and, each has a role to play in this world, in her/his own manner. Each should choose her/his path in the most essential mission of all – the discovery of one’s true Self. The Gita, broadly, lays down these paths as four – Jnana, Bhakti, Karma and Yoga. These paths are neither mutually exclusive, nor do they contradict each other. They are meant to be guide posts that direct us along the paths that best suit our nature and attitudes.

Jnana Yoga is the intellectual path demanding that one apply reason and rationale in order to realize her/his essential core; and, understand her/his relation with the world and god. It is a lonely path of self- discovery. It is the discipline of knowledge of Self. It also means knowing clearly; realizing one’s own divinity; and, also seeing the divine in human and the earthly.

Since we do have to exist , act and participate in this world , in a meaningful manner, understanding the true connotation of the path of Karma is essential. Karma is the way we conduct our lives , performing activities , fulfilling our roles and responsibilities towards self , family and the society at large; following a path of righteousness directed towards improving ourselves. While one should act diligently, one should not be overly attached or obsessed with the fruits of one’s actions. The detached attitude towards the results, might, initially, appear to be a counter-intuitive or contrary to common-sense ; but , on reflection , one would realize that it is the most efficient and clear-headed way to stay focused on the task at hand. The ability to maintain equanimity at good and bad times , even otherwise, marks a balanced approach to life.

The first-half of the Gita essentially teaches a combination of Karma-yoga and Jnana-yoga- to act selflessly with true knowledge of the reality. Here, Equanimity serves as a foundation standing upon which one can look beyond and reach for a reality that is totally different, the Absolute.

Though the wise one fights battles, he does it with composure , devoid of enmity or hate , rancor or self-interest. The enemy, after all, is as much a manifestation of God as the warrior is.

The Bhakti-yoga is the path of love, immersing oneself in the boundless Love of God and, submitting to Him in artless faith and absolute devotion . It aims to experience the splendor of the divine in all its manifestations (Lila), and immerse in its delight (Ananda).

The Dhyana–yoga or Raja-yoga, the Royal way, is the discipline of meditation, withdrawing the senses, calming the mind and clearing it of confusions and other delusions. The path of Yoga is a method for controlling the waves of thoughts, and the senses; refining the mental and the physical energy. It seems to be based in the eight-fold (Astanga) Yoga system of the Sage Patanjali, though there are no explicit references to it; and, there are also no separate verses or chapters devoted to this discipline

*

Arjuna begins in bewilderment and depression; and at the end, stands up to fight his cousins with composure.

[One of the commentators observes: assuming that the Gita was an insertion into the Epic; and, given the fact that the great battle did eventually take place, the outcome of the Gita could not have been different. Arjuna had to fight, in any case.]

Synthesis

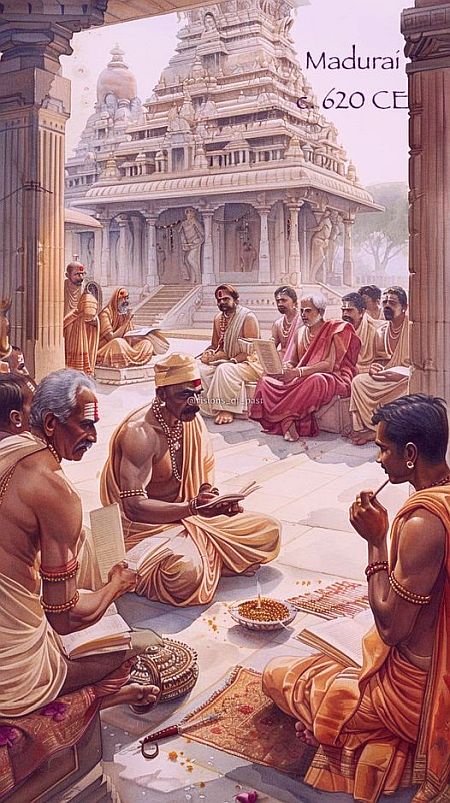

It appears that the Bhagavad-Gita was composed during a vibrant period when growing verities of options for attaining liberation (Moksha) from confines of human limitations were hotly debated and ardently explored.

Bhagavad-Gita frequently refers to the fundamental philosophical concepts of Samkhya and Yoga Darshana-s. It is also based in many Upanishads providing verities of solutions to human predicaments, as also suggesting pointers to the understanding of the Universe, the individual and the relation that exists between the two. The Bhagavad-Gita, in that process, draws upon many sources.

In that progression, the Bhagavad-Gita elaborates on the varied disciplines and paths of Jnana (knowledge), Karma (action), and Bhakti (devotion) as also Yoga for attainment of the highest good. The text calls itself Yoga-shastra – the science and knowledge of Yoga.

The term Yoga is used in Gita in a variety of senses. And, Yoga here also stands for Marga, the path; be it the path of knowledge (Jnana-yoga), devotion (Bhakthi-yoga) or the path of action (Karma-yoga). In all these paths, the essential message of renouncing the fruits of action is stressed.

The Gita does not explicitly support one Yoga over the other. It rather extols one Yoga then another or a combination of Yogas. It is to be understood as a many-sided system with various elements juxtaposed.

*

Justice Kashinath Triambak Telang, in his introduction to Bhagavad-Gita (Oxford, New Clarendon Press, 1875/ 1882) ,writes :

The Gita offers a set of practical disciplines, without, however, attempting, to arrange or classify them in a systematic order. In other words, what we have in the Gita is the germ of the ideas or of the systems; but not a ready-made system as such.

There are also certain passages in the Gita, which do not easily reconcile with one another. And, the Gita makes no attempt to harmonize them.

For instance; Krishna classifies the devotees into four classes; and, says that he considers the Jnanis (the persons of knowledge) as his own (Gita – Ch .7-verse 16). This might give an impression that he places the Jnanis at the top of hierarchy. But, again he remarks elsewhere that the devotee (Bhaktha) is superior not only to those who merely perform penance; but , also to the men of knowledge (Gita-Ch.6-verse 46). And, in another passage, it is said that concentration is preferred to knowledge (Gita-Ch.12-verse 12).

All these indicate the Gita, as do the Upanishads, is a remarkably free, open-ended un-systematized work.

Does not seem to favor a particular path

The discourse on those subjects, however, is not arranged in a systematic manner. The Gita gathers and combines different trains of ideas just as it finds them in traditionally accepted Schools, without much effort to harmonize them. The text does not seem to hold up a single discipline or path as its ‘true message’. And, such ambiguity in its ‘message’ or the adaptability of ‘its message’ to different Schools of Philosophy and to the circumstances in life has led to plethora of interpretations, each claiming that it has certainly grasped the ‘true message ‘of the Bhagavad-Gita.

One can even say that the scope for deriving varied types of interpretations becomes possible mainly because of the unique virtue of the Gita which allows each reader to discover its essence, in his or her own manner, at his or her own pace and terms.

Deciphering its meaning and its ‘true’ philosophical intent is neither easy nor simple. Some of the greatest minds have grappled with the philosophical problems present in it.

The ways of reading the Gita

There are several ways of reading Bhagavad-Gita. It can be read as a literary work or poetry of merit with allegorical imagery; it can be read as a part of Oriental studies; and, it can also be read as a philosophical work.

As a work of literature, its literary or poetical aspects would be discussed and the allegories would be highlighted. As a work of Indology, its historical background and linguistic aspects would be examined. Such a scrutiny would focus on the date of its composition; on speculations about its plausible author or author/s; or on the question of its relation to the context of the Mahabharata-events.

But, it is the study and explanations of Gita’s philosophical outlook, its conceptual structure and speculations about its ‘true message’ that has given rise to diverse stand points and multiple interpretations. Such interpretations over the centuries have been so diverse and so complicated, that it makes one wonder whether they all were referring to one and the same text.

The Gita’s adaptability to different kinds of philosophical interpretation is partly caused by the effort of its composer/s to bind within it the tenets of several philosophical schools (Darshana-s) including Samkhya, Yoga and the devotional aspects of the then emerging Bhakthi traditions. That, to an extent, injected ambiguities and incompatibilities in reading and interpreting the text.

The phenomenon of multiple interpretations of the Gita has continued over the long centuries. At different times or phases in the history, fresh interpretations of the ‘true message ‘of the Gita sprang up, each in the context of its own times, environment and preferred attitudes. Each successive interpretation of the Gita was at variance with its previous one. And yet, what is most amazing is that each of those varied interpretations is valid in its own context.

That is to say; each commentator has diligently gone about in putting forth his honest understanding of the ‘true message’ of the Gita. Each commentary of the Gita is thus a subjective view of the text. The ‘message of the Gita’ might indeed be all of those assorted interpretations; and, even be more.

The quest for objective truth or the real truth of the Gita is still very much on, even thousands of years after it was uttered on a distant battle field, amidst two huge armies raring to go at each other.

Quest for objective truth

The quest for objective truth – (what did Krishna say, exactly?) – is another cause for emergence of multiple interpretations and countless number of commentaries. In the zeal to uphold his own interpretation as the objective truth of the Bhagavad-Gita, each commentator, somehow, seemed to get intolerant of the ones that differed from his own. That, in a way, is rather uncharacteristic of the Indian tradition which accommodates within itself and harmonizes various seemingly contrary positions.

All the branches of Indian traditions, notably the Jain, have always tried to adopt the concept of Anekāntavāda which, essentially, is a principle that encourages acceptance of multiple or plural views on a given subject. The Buddha too said that merely judging the issue from individual (separate) stand points of view would lead to wrong conclusions; it would be prudent to approach each issue from more than one point of view (aneka-amsika).

[Devadatta Kali (David Nelson) in the introduction to his very well written work Svetasvataropanisad: the Knowledge That Liberates writes:

Although the Indian thinkers are not immune to disputation , by and large , their culture has valued the principle of accommodation and acceptance…Throughout the centuries of Indian philosophical traditions , the differing views have often been seen as just that – as differing views of a single reality that lies beyond human power of articulation. The tendency has often been to harmonize opposing views as distinct parts of a larger whole whose fullness lies well beyond the reach of mere perception or reason. It needs to be stressed that the primary purpose of sacred literature is to impart spiritual knowledge, not to fuel intellectual or sectarian debate – or to create confusion.]

The basic idea here, is that the reality could be perceived differently from diverse points of view; and, that no single point of view should be taken to be the complete truth, to the exclusion of all others. The varied views could either be taken together to comprise the complete truth or as different dimensions of a single reality.

Bhagavad-Gita is a multi-layered text with many avenues for exploration. I , therefore, reckon that an Anekāntavāda approach would be more appropriate in understanding its manifold message, rather than steam- pressing it into a particular mold.

[Please listen to Dr. Karan Singh speak about Bhagavad-Gita : Click here

You may then opt for the Mini-view ]

Is there a need to seek for the ‘objective-truth?’

That again begs the question: is there a need to seek for the ‘objective-truth’ of the Gita? Because, there is a danger that such monolithic one’s own ‘objective–truth’ might shut out the options of myriad other plausible meanings. Thus, a purely objective view, despite its merit, seems to limit itself to a particular slot.

There is, therefore, surely some merit in subjective approach to the study and understanding of the Gita. In fact, some have suggested that each could try to compose his own Gita according to her/his own understanding and inclination.

As Shri Devdutt Pattanaik observes: The quest for subjective truth (how does The Gita make sense to me?) allows each (after listening to the various Gita-s around him/her) to discover one’s own Gita at his or her own pace, on his or her own terms.

The Gita itself seems to advocate subjectivity. Bhagavad-Gita in its structure and narration adopts the idea of free-will. At the conclusion of his discourse, Krishna counsels Arjuna to reflect on what has been said, and then do as he rightly feels.

For instance; Krishna says that his teaching can be perceived directly (Pratyaksha-avagamam) according to one’s understanding (BG.9.2)

राजविद्या राजगुह्यं पवित्रमिदमुत्तमम् । प्रत्यक्षावगमं धर्म्यं सुसुखं कर्तुमव्ययम् ॥ २ ॥

rājaguhyaṃ pavitram idam uttamam / pratyakṣā-avagamaṃ dharmyaṃ / susukhaṃ kartum avyayam 9.2

And again, in Chapter 12 of the Gita, Krishna counsels:

Fix your mind on me alone, and absorb your consciousness in me; thus you shall surely abide in me. If you cannot fix your consciousness steadily upon me, then aspire to reach me through repeated yoga practice. O Dhananjaya, if you are incapable of even that, embrace the path of action, for which I am the highest goal, since by acting for me you shall attain perfection. But if you are unable to follow even that path of refuge in me through acts devoted to me, then give up the fruits of all your actions, thus restraining yourself. Knowledge is superior to practice; meditation is superior to knowledge; and, relinquishing the fruits of action is higher than meditation, as tranquility soon follows such relinquishment.

What really is the true vision or Darshana of this ancient, sacred and marvelous treatise named Bhagavad-Gita, the song celestial?

Pluralism of the Gita

How does the text permit such a range of interpretations? What is common to them? How is it possible for so many to provide their own interpretations while still claiming to be reading “the Gita”? Why did this one text in particular exercise such fascination on so many generations of Indian and non-Indian thinkers? How could Bhagavad-Gita lend credibility or even moral authority to political movements in modernity? And , did they all use the text in their own way, in order to somehow secure Krishna’s divine authority ? !

Heinrich Von Stietencron , addressing such an array of bewildering questions, writes:

The analytic thinking of Western interpreters who were schooled in historico-philological methods stands in contrast to the traditional Indian commentators, who not only harmonized and freely covered over all breaks in the text of the Bhagavad-Gita, , but, above all, sought to read their own philosophical-theological concepts out of individual textual passages, in order to secure Kṛṣṇa’s divine authority for them.

In this manner, several philosophical schools developed their own Gita -interpretation — a spectrum that has, since the beginning of India’s independence movement been further supplemented by politically motivated interpretations in modernity.

The multiple interpretations or pluralisms of approaches in understanding the Bhagavad-Gita have an extensive and illustrious history. During that long period, different aspects of the Gita came into the fore; new meanings were read into its passages; and attempts were made to adopt its ‘message’ to suit new or emerging situations.

The history of the interpretations of the Gita can broadly be considered under the following heads:

: – The Acharyas

The medieval period starting with Sri Sankara (8th century) followed by the Bhashyas of Sri Ramanuja , Sri Madhwa and other Acharyas as also that of Abhinavagupta analyzed and commented upon the Gita in terms of the traditional Vedanta concepts of Advaita, Visistadavaita and Davaita; and assigned primacy either to Jnana (knowledge) or to Bhakti (devotion) or to Karma (action) . Each scholar went according to the principal philosophical precept of his School of thought , while sidelining the other plausible interpretations .

Santa Jnanesvar or Jnanadeva (1274-1297) of Maharashtra in his celebrated rendition of the Bhagavad-Gita – Jnaneshwari (Bhavarth Deepika) – taught the path of loving and guileless devotion (Akritrim Bhakthi) and self-less action as the true way. He said that everyone should perform his/her duty lovingly as a Yajna and offer his or her actions as flowers at the feet of the Lord. According to Jnanadeva; it is through such Bhakthi and Bhakthi alone that the Supreme Reality can be realized

: – The Colonial period

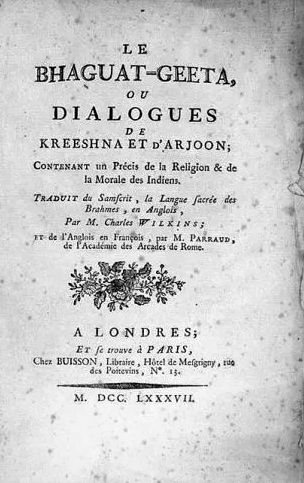

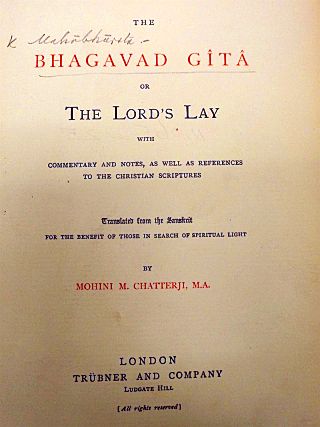

The period starting with the middle of the 18th Century when the English, German and French translations of the Bhagavad-Gita , captured the attention of the intellectuals as also that of the general-readers, widened the range of its readership as also the scope for its varied interpretations.

: – Initially, Bhagavad-Gita gained publicity mainly as a rare cultural object retrieved from the unknown past of the distant East; and , in particular , as ‘a curious specimen of mythology and an authentic standard of the faith and religious opinions of the Hindoos’.

: – That was followed by study of the Gita as a literary work. It proved to be a major influence on Romantic literature in Europe and Britain.

: – And, to the intellectuals and philosophers in the West, the Gita provided a perceptive view of the Hindu philosophy. Among the scholars, the linguistic study of the Sanskrit text of the Gita; the historicity of the Mahabharata event; the questions of its authenticity and its date; the enquiry into its plausible author /authors and so on were widely discussed.

:- The Gita evoked a different sort of reaction among the Christian Missionaries , They saw in it a possibility ’ to encourage a form of monotheist ‘Unitarianism’ ; to draw Hindus away from the polytheism of the Vedas’; and, to pave way to spread Christianity in India.

:- As the English and French translations of the Gita began to gather attention from among the educated class of the Colonial India of the 19th Century , it led to review and re-assessment of the principles of the Hindu philosophy and the practices of its faiths . The Western educated intellectuals and social reformers such as Raja Ram Mohun Roy regarded it as the essence of all Shastrus; and. interpreted Gita as a message for self-less action.

Though the Brahmo Samaj did not seem to have got the Gita translated , Debendranath Tagore tried interpreting Gita , in the Biblical mode, as a sort of allegory depicting the final battle (Armageddon) between the forces of ‘good’ and ‘evil’.

: – The Western scholars

Following its translations into European languages, the Gita gained a sort of territorial transcendence, spreading its influence beyond Asia. The Gita came to be regarded by the western scholars as a universally acclaimed text.

Among the Western scholars, the Bhagavad-Gita came to be looked upon as the authentic essence of Hinduism. And, and it became the most influential work on Indian thought. The German philosopher William Von Humboldt called Gita: the most beautiful, perhaps the only true philosophical song existing in any known language –the deepest and most elevated text the world has ever seen. He was fascinated by its concept of Dharma delineated in various layers.

Similarly , TH Griffith saw Yoga taught in the Gita as the discipline of life, giving a deep insight into the ebb and flow of human desires and aspirations.

And, the German Indologist JW Huer described Gita as a ‘work of imperishable significance’ calling upon people to ‘master the riddle of life’.

Max Muller too believed ‘that textual authority of Gita should have pride of place in official knowledge about India’; but, he placed Gita next to Vedas in its authority and importance.

[Prof. Hephzibah Israel of the University of Edinburgh, in her paper The Politics of the Gita in English Translation: Translating the Sacred, colonial constructions and postcolonial perspectives, writes

The Bhagavad-Gita was first translated into English by Charles Wilkins in 1785; and, into the German, either in part or in full , by Friedrich Majer, Johann Gottfried Herder (1792), and Friedrich Schlegel (1808); and in full into Latin by August Wilhelm Schlegel (1823). And, it continued to be the object of translators’ attention throughout the nineteenth century.

German scholarly attention to the philological apprehension of Indian sources is linked to Indology, and to comparative linguistics and the study of religion. In fact, as a result of this early German philosophical engagement with the Bhagavad-Gita,

The text not only continued to be translated by both British and Indian scholars but was also accorded a Bible-like status; although Hindu Indians had not , hitherto, perceived it as such. The Orientalist desire for textual representations of the East can be “intimately connected to the desire among Hindu scholars to have scriptures, like Christianity and Islam”

Significantly, the Bhagavad-Gita was ascribed high status in Britain and Germany by being treated as a self-contained philosophical text, rather than as an integral part of the much longer Mahabharata, one of the two Hindu epics that in popular Hindu formulations are considered foundational texts representing the “Indian nation” and its “culture.”

This is clear in the number of translations of the Bhagavad-Gita alone, singled out for attention with only brief reference to the larger text that it is embedded within. Unable to come to terms with a Hinduism that did not claim a single authoritative scriptural text, Orientalist scholarship reconfigured the existing sets of sacred texts through translation to bring forth a “central text” that could be identified as a higher foundational document. Examining para textual evidence such as titles, translator’s notes, prefaces, and introductions gives us a good indication of the purpose of a translation and how it was meant to function.. ]

**

: – The Theosophists

The Theosophists recognized the Bhagavad-Gita as one of the major spiritual texts of the world. Among the Theosophists, the allegorical approach with its esoteric and philosophical interpretations gained more importance. The historical and mythological context was kept in the background just to explain the context of the Gita.

According to them, Krishna in the Gita represented Logos the objective expression of the Absolute; while Arjuna represented the Monad, Nara, the whole of mankind rather than as a single person.

They explained life as an evolutionary process in which an individual evolves from lower to higher, from grosser physical forms to subtle spiritual forms of beings. The Gita, according to Theosophists , is a framework for such a progression.

Theosophists interpreted the concept of one’s duty in terms of the Sva-dharma. They presented the world as a conditioned reality similar to a huge game in which each piece must move in accordance with the rules governing its movements in order to keep the game going.

: – Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda , while in the West, compared Krishna’s teachings to that of Jesus. And, while at Home , he spoke about the inner battles in human heart and mind. And , he also described Krishna and Arjuna as men of action who could provide inspiration to reform and rejuvenate the Indian society that was fast degenerating into chaos and confusion. He called for resistance against British oppression.

While laying more importance on the Gita’s larger allegorical meaning, Swami Vivekananda acknowledged the validity of historical research. But, he also said that mere discussion on the historical aspects of the Gita cannot help one in acquisition of Dharma, or moral righteousness’.

The idea is: the Bhagavad-Gita is not merely a historically specific conversation; but, it is an ongoing teaching that has universal relevance. It is a process taking place all the times in each ones heart.

He remarked:

“One thing should be especially remembered here, that there is no connection between these historical researches and our real aim, which is the knowledge that leads to the acquirement of Dharma. Even if the historicity of the whole thing is proved to be absolutely false today, it will not in the least be any loss to us. Then what is the use of so much historical research, you may ask. It has its use, because we have to get at the truth; it will not do for us to remain bound by wrong ideas born of ignorance.”

:- Sister Nivedita

Sister Nivedita (Margaret E. Noble , 1867-1911) considered not the withdrawal from the world; but, performing ones duty , while in it, diligently and selflessly, without attachment to consequences – as the message of the Gita.

In her very well written book ‘The Web of Indian Life’, under the Chapter: The Gospel of the Blessed one (page 217) , wrote:

*

The book is nowhere a call to leave the world; but, everywhere an interpretation of common life as the path to that which lies beyond…

That the man who throws away his weapons ; and, permits himself to be slain , un-resisting in the battle , is not the hero , but a sluggard and a coward; that the true seer is he who carries his vision into action , regardless of the consequences to himself. This is the doctrine of the Gita repeated again and again

‘Holding gain and loss as one, prepare for the battle’. That indifference to results is the condition of efficient action is the first point in its philosophy… It is the supreme imperative. Play thy whole part in the drama of time, devoting every energy, concentrating the whole force. “As the ignorant act from selfish motive, so should the wise act unselfishly.”

[Eminent Orientalists: Indian, European and American. pages 268-269]

: – The Nationalists in the Freedom movement

While the Theosophists tried to provide allegorical and esoteric interpretations of Gita as spiritual struggles, the Nationalists in the Colonial India of the 19th and early 20th century mainly from Bengal and Maharashtra saw it in quite another manner.

The freedom movement gave a great impetus to the study of Gita. Many saw it as a national symbol that held within its bosom answers to the burning questions of colonial India. The Key word from the Gita taken by the nationalists was Loka-sangraha – welfare or involvement in the world. That phrase occurs only two times in the Gita (3.20, 25).

कर्मणैव हि संसिद्धिमास्थिता जनकादयः । लोकसङ्ग्रहमेवापि सम्पश्यन्कर्तुमर्हसि ॥ २० ॥

सक्ताः कर्मण्यविद्वांसो यथा कुर्वन्ति भारत । कुर्याद्विद्वांस्तथासक्तश्चिकीर्षुर्लोकसङ्ग्रहम् ॥ २५ ॥

Then, there also came into use an expression that is not found in the Gita . It gained much currency in the 20th century – Nish-Kama-karma, self-less action.

Linking of these concepts with national movement for Independence and social reforms did much to bring forth Gita into popular debates. The nationalists promoted Gita as a central work of a rising Indian national ethos.

It is indeed remarkable that so many of India’s political and intellectual leaders of the last century and a half wrote detailed and extensive commentaries on the Gita. There were two broad categories of interpretations.

One; as a sort of romantic allegorical visions of the battle against forces of lower tendencies such as greed, ego, selfishness etc; and, the other, as an authentic source of state craft that prompted to reconsider the nature of politics itself .

The latter, led to gathering support for reform efforts and for justifying a fight against the British rule for attaining independence.

Among the former category, Bamkim Chandra Chattopadyaya (1836-1894) provided great inspiration for the National movement, giving impetus to the concept of Motherland as the Goddess India, Mother India. He also depicted Krishna as the ideal person who exemplifies human virtues – a god-like person who was earthly wise and sublimely spiritual in his core. He projected Gita as an answer to West’s technological domination; and as India’s stand asserting the merits of ancient wisdom in the face of colonial oppression.

*

Sri Aurobindo, who followed Bamkim Chandra, regarded Gita as an absolutely splendid revelation holding forth a Universal message. He advised that Gita should be approached by forgetting all the religious and academic arguments that highlight or decry one Yoga (paths) or the other. The integrated vision of the Gita, he said, transcends all such limited interpretations. He envisioned Gita as a divine action, where the battle field (Krukshetra) is in the heart and soul of every human being. Each one of us, potentially brave, fights in his or her own way with the confronting doubts, desperation, fears and frustrations. Krishna is the one, hidden behind the veils of our psyche and mind, who reveals the mysteries of life. Sri Aurobindo stressed that in the present age it was necessary to understand the Dharma, Karma and Yogas in contemporary sense.

Sri Aurobindo, who followed Bamkim Chandra, regarded Gita as an absolutely splendid revelation holding forth a Universal message. He advised that Gita should be approached by forgetting all the religious and academic arguments that highlight or decry one Yoga (paths) or the other. The integrated vision of the Gita, he said, transcends all such limited interpretations. He envisioned Gita as a divine action, where the battle field (Krukshetra) is in the heart and soul of every human being. Each one of us, potentially brave, fights in his or her own way with the confronting doubts, desperation, fears and frustrations. Krishna is the one, hidden behind the veils of our psyche and mind, who reveals the mysteries of life. Sri Aurobindo stressed that in the present age it was necessary to understand the Dharma, Karma and Yogas in contemporary sense.

*

The more militant among the Indian nationalists projected India as the Motherland and Krishna as Avatar who rescued the nation from jaws of A-dharma and to establish Dharma. They accepted the call of the Gita for righteous struggle for national independence, even if it might require violence. The new battlefield, according to them, was the British Raj; and , they found in Gita a strong support for engaged social and political action, the karma yoga.

Lokamanya Bal Gangaadhar Tilak, who at that time was imprisoned in Burma, presented Gita as an allegory for fighting a just war (Dharma-yuddha) that historical circumstances had forced upon Indian nation and Indian people. In Tilak’s view, interpretation of a religious work like the Gita must be historically situated. He vehemently argued for an activist or “energist” reading of Krishna’s teachings, against the older “escapist” Vedanta interpretations. And, in the present age , he asserted, the Gita must be interpreted in accordance with its needs. Like Aurobindo, Tilak accepts that this action might include violence, provided it is carried out without hatred and without any desire to reap the fruit of the violent deeds. He also admits : But herein lies a quandary of dharma.

It needs to be mentioned ; even while calling for a just war (Dharma-yuddha), these commentaries did maintain a sense of composure and detachment. Just as Arjuna did not regard his warring cousins as foes, the British were also not targeted as the ‘enemy’; not because of fear, but in the interest of generating a broad theoretical principle for establishing a basis for their political ideology and its strategy. Such an approach allowed Indian leaders to outline a political framework that would serve them well even beyond and after imperialism.

At the same time, at the ground level, there were also groups, organized or otherwise, that believed in disruptive violence as the effective means for overthrowing the alien imperialist power.

In either case, the Gita provided a stable point of conceptual references, even while there was a range of multiple interpretations on the related issues.

[The practical question for Tilak and other activist leaders was how to mobilize larger masses on behalf of the struggle for an independent Indian nation. Throughout his career, Tilak experimented with ways to enlist the Indian population in this effort. In the 1890s, he transformed a local Maharashtrian festival for the god Ganesha into a large public celebration; and , he established a new festival to honor Shivaji.

Similar methods were adopted in Bengal by transforming Durga-Puja into a national festival. And, in Punjab , Baishaki was turned into a celebration for all.]

[ Prof. Hephzibah Israel concludes:

Both European and Indian translators, by choosing to translate the Bhagavad-Gita, established it as the quintessential “Hindu” text and as a representative of a highly complex quasi-philosophical and quasi-mystical text which conferred on Hinduism status as a “world religion.”

While for Orientalist scholars, the translated Bhagavad-Gita was proof of an ancient and glorious “civilization,”.

For missionary translators, the Bhagavad-Gita was a philosophical text ; and not necessarily a sacred “scripture.”

However, for the Indian translators, also mostly practicing Hindus, translating the Bhagavad-Gita was simultaneously an appropriate gesture and an opportunity to compete in the world hierarchy of “religions”: having for centuries preserved the Bhagavad-Gita in the exclusive Sanskrit. The Indian scholar-translators were embracing the opportunity to translate the text mostly into English rather than into other Indian languages.

While some translators, argue that they translate to educate fellow-Indians, to spread the “truths” of Hinduism to Indians, ,, their energies seem directed equally at non-Indian readers.

The appropriation of translation as a strategy to re-present Hinduism was a response to the Universal idea of religions that has often been played out through assumptions about their translatability. This deployment of translation has been an important factor in the formulation of resistant alternative colonial discourses.]

***

: – Gandhi

Though all the nationalist leaders agreed that purposeful action was needed to attain independence, the form that such action should take, however, remained a point of heated contention. This is where the faith and the views of Mohandas Gandhi become very significant.

Gandhi often referred to the Bhagavad-Gita as his “spiritual reference book” ; “dictionary of daily reference”; “book of home remedies”; “wish-granting cow”; and, as “mother”. He returned to it over and over again throughout his life for clarification and nurture. He spoke and wrote widely on it throughout his career.

Gandhi, in contrast to other major nationalist leaders, held no commitment more important than to his principle of non-violence. But, he ran into a serious interpretive problem because in the course of the Gita Krishna persuades the reluctant warrior Arjuna to take part in an internecine disastrous battle.

Gandhi believed that the message of the Mahabharata itself was the virtues of non-violence; and, the Gita which was but a small segment of it carried a similar message. He wrote:

the author of the Mahabharata has not established the necessity of physical warfare; on the contrary he has proved its futility. He made the victors shed tears of sorrow and repentance; and has left them nothing but legacy of misery.

The question whether the true teaching of the Gita favors violence or non-violence became vitally important to Gandhi. He needed a clear , firm and an honest answer to anchor his faith in his struggle for India’s freedom ; to provide a principled public resistance; and, above all to ensure the authenticity of his inner spiritual life. The Gita, as he understood and practiced, was the foundation of his struggle without hatred, without passion (Nish-Kama-karma) with the attitude ‘mine is but to fight for my meaning, no matter whether I win or lose.’

And, that led Gandhi to offer a particularly distinct interpretation of the Bhagavad-Gita, where Krishna instead of asking Arjuna to fight the war, instructs him to ‘fight the battle within the self; to battle passion and selfishness’.

According to Gandhi, Gita demonstrates the futility of violence; and, its true message is non-violence and peace. At the end of the Mahabharata, nearly everyone on both sides is killed

Gandhi said, it was fought “not to show the necessity or inevitability of war, but to demonstrate the futility of war and violence.” This becomes evident in Shanti Parva, where “at the end, the victor is shown lamenting, and repenting, not only the outcome, but the very idea of causing so much pain, such horribly enormous devastation and violence”.

Supporting Gandhi’s view, ‘The Epic’, writes Amartya Sen, ‘ends largely as a tragedy, with a lamentation about death and carnage; and , there is anguish and grief … It is hard not to see in this, something of a vindication of Arjuna’s profound doubts.’

The battlefield, Gandhi argued, must be taken as an interior one, where the forces of good and evil are locked in never-ending struggle. The Bhagavad-Gita, he said, is not about the battle that is waged on the field of dirt soaked in blood; but, it is about the ever going conflict within the human heart between the forces of good and evil.

Gandhi said; when Krishna asked Arjuna to fight, he meant fighting ones lower impulses; not to cling to its rewards; to overcome any self-interested inclinations; and, to carry out his own righteous duty. One must be equally disposed to ones enemy as to oneself.

Gandhi based his own authority as an interpreter of the Gita on his personal endeavor “to enforce the meaning in my own conduct for an unbroken period of forty years.” Gandhi also claimed that the Gita was not a Hindu work, but rather one of “pure ethics,” which a person of any faith might read and follow.

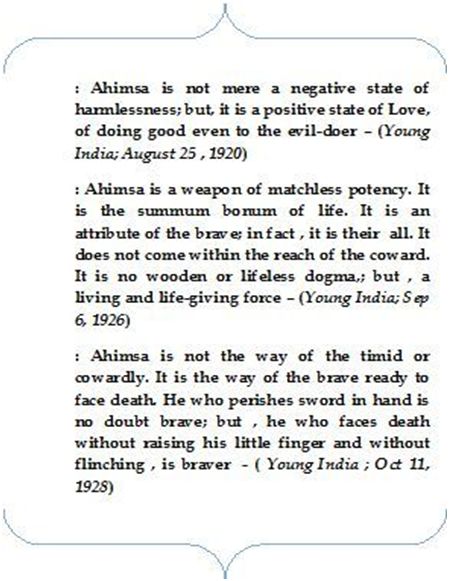

Gandhi firmly believed that complete renunciation is not possible without total observance of Ahimsa (non-violence) in every form and shape.

Gandhi said that if one has to fight, one should fight non-violently. Thus, Violence and denial of violence became major issues for debate and action.

Gandhi’s faith in Ahimsa as the core of the Gita gave rise to Satyagraha , as an effective means to express one’s protest and to offer resistance without indulging in violence. According to him, a Satyagrahi should be willing to die like a soldier (Kshatriya) for the cause of India’s independence. Satyagraha was Gandhi’s unique contribution to fight against oppression and injustice.

This was in sharp contrast to the interpretation offered by the leaders of India’s nationalist movement such as Sri Aurobindo and others to fight a just war for liberating the Motherland. In fact, during Second War Sri Aurobindo called on Indian people to support the British in its war efforts and fight along with the British against fascist Germany.

: – Aldous Huxley

Similarly, in Aldous Huxley’s famous introduction to the translation of the Gita by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood (The Song of God: Bhagavad-Gita, Hollywood: M. Rodd Co., 1944) which was published just after the end of World War II, the questions of war, violence gained special significance. Writing in the midst of a war of destruction and violence on an unprecedented scale, Huxley re-read and re-imagined the Gita in a mode which rejected the utter need to kill. He, like Gandhi, emphasized that the true message of the Gita is not violence; but, on the contrary, the futility and uselessness of violence, self-destruction; and, the harm it can bring upon whole generations.

On July 16, 1945, at the dawning of the atomic age, J. Robert Oppenheimer watched the first human-controlled atomic explosion at Los Alamos, New Mexico, from a bunker twenty miles away. As director of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was responsible for overseeing the creation of the bomb, which the project called “Trinity.” He was a brilliant professional physicist, and also a gifted amateur student of Sanskrit. As he observed the awesome detonation of Trinity, Oppenheimer later recalled that passages from the Bhagavad Gita sprang to his mind.

On July 16, 1945, at the dawning of the atomic age, J. Robert Oppenheimer watched the first human-controlled atomic explosion at Los Alamos, New Mexico, from a bunker twenty miles away. As director of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was responsible for overseeing the creation of the bomb, which the project called “Trinity.” He was a brilliant professional physicist, and also a gifted amateur student of Sanskrit. As he observed the awesome detonation of Trinity, Oppenheimer later recalled that passages from the Bhagavad Gita sprang to his mind.

If the radiance of a thousand suns / Were to burst at once into the sky / That would be like the splendor / Of the Mighty One … / I am become Death / The shatterer of worlds

दिवि सूर्यसहस्रस्य भवेद्युगपदुत्थिता ।यदि भा: सदृशी सा स्याद्भासस्तस्य महात्मन: ॥ १२ ॥

Divi surya sahastrasya bhaved yugapad utthita / Yadi bhah sadrashi sa syat bhasastasya mahatmanah (BG.11.12)

कालोऽस्मि लोकक्षयकृत्प्रवृद्धो लोकान्समाहर्तुमिह प्रवृत्त: । ऋतेऽपि त्वां न भविष्यन्ति सर्वे/येऽवस्थिता: प्रत्यनीकेषु योधा: ॥ ३२॥

’kālo ’smi loka-kṣaya-kṛt pravṛddho/ lokān samāhartum iha pravṛttaḥ / ṛte ’pi tvāṁ na bhaviṣyanti sarve/ye ’vasthitāḥ praty-anīkeṣu yodhāḥ ॥

: – Allegorical Interpretations

Since the early periods the allegorical interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita have been in vogue, by looking upon Kurukshetra as not a mere geographical region or historic battle.

Abhinavagupta, in his Gitartha-sangraha, a commentary on Bhagavad-Gita, refers to a tradition of interpreting Kurushetra as zone of war that takes place between the righteous and un-righteous tendencies within the human body. According to him, Kurushetra is something more than a geographical venue where a battle took place among the cousins and their supporters.

Similar allegorical interpretations of the Gita became quite a regular feature by the turn of the nineteenth century; and it has been carried forward ever since. Such interpretations fall in to two broad categories: One, to battle against forces of lower tendencies such as greed, ego, selfishness etc; and, the other, to gather support for reform efforts and for justifying a fight against the British rule for attaining independence.

For Sri Aurobindo, ‘the physical fact of war is only an outward manifestation of a general principle of life. The war symbolizes all aspects of struggle that takes place all the time, both in our inner and outer living.. Life is a battle and a field of death; this is Kurukshetra’.

For Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Kurushetra signified Dharmakshetra, a just war against oppressive foreign rule.

Edwin Arnold too referred to Kurukshetra as human body, the field where Life disports.

Gandhi followed Arnold’s interpretation that Kurukshetra is where an eternal struggle is taking place within us.

The present-day

In the present day, the discussions about Bhagavad-Gita in terms of Advaita – Dvaita; or Jnana-Karma-Bhakti have become very rare. The focus is now more on Gita’s stand on the question of violence; whether it advocates or shuns violence; the efficacy or the moral justification for resorting to violence as a vehicle for expressing one’s protest against the establishment.

There are a notable few who adopted the Gandhian method of Ahimsa to fight against oppression. The celebrated ones among such votaries of non-violence are: the HH the Dalai Lama the spiritual leader of the displaced Tibetans who firmly believes that the all-embracing ‘concept’ of Ahimsa is the proper solution for any human conflict; Dr. Martin Lather King who led the civil disobedience movement against racial discrimination; and, Aung San Suu Kyi the Burmese nationalist leader who influenced by the philosophy of non-violence of the Buddha and of Gandhi chose non-violence as an expedient political tool in her struggle for democracy and human rights.

In India, we have the dauntless lady, Irom Sharmila from Manipur who during August 2016 quit her 16 long years of fast demanding repealing of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. We also have Anna Hazare who largely adopted non-violent protests and hunger strikes (a la Gandhi) in his struggles to promote rural development, to increase government transparency, and to investigate and punish corruption in public life etc. And, there is Medha Patkar, the resolute social activist and social reformer, ever engaged in various protests. These and such other well-meaning protesters, sadly, have not met with much success.

Apart from these and few others there is hardly any who has earnestly adopted Ahimhsa in her/his struggle against injustice. The Gandhian way seems to be losing its ground in India. This seems to reflect the state of our being; the times we live in; and, the values we cherish.

Let’s take, for instance, the Indian situation.

The India of the present-day is no longer under foreign rule. It is now governed by the political parties elected by the Indian citizens. The question is: whether one is entitled or justified for expressing dissent in a violent manner. The question was answered by a resounding YES by the Naxalite and such other militant groups. They sought to find moral justification for taking up arms by quoting Bhagavad-Gita.

A similar justification is made out by the Jihadist terrorist groups who, strangely, also quote the Gita for carrying out their violent attacks.

Even the protests involving inter state river-water disputes, social injustice etc is marked by violence and vandalism destroying public property.

: – There are also those who denounce the ‘message of the Gita’ for various reasons.

For instance:

Mahatma Jotiba Phule (1827-1890) who was a pioneer in raising awareness of the rights of the Shudras and Ati-shudras (OBC and SC, as classified now) regarded Manu Smruti and the Gita as signs of slavery (Gulamgiri).

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, in his writings on the Gita, insisted that it be seen as a historical work, composed at a certain time, and he criticized those who sought to give it a universal significance. He argued, the Bhagavad Gita was a counter revolutionary. In his essay, Krishna and His Gita, Dr. Ambedkar wrote, ‘The philosophic defense offered by the Bhagavad Gita of the Kshatriya’s duty to kill is, to say the least, puerile.’

The infamous Wendy Doniger has said: “The Bhagavad-Gita is not as nice a book as some Americans think. Throughout the Mahabharata, Krishna goads human beings into all sorts of murderous and self-destructive behaviors such as war. The Gita is a dishonest book.”

And, Meghnad Desai, economist and politician, in his Who wrote Bhagavad-Gita, declared the Gita as ‘unsuitable to modern India’ whose Constitution commits it to ‘a world of social equity and democratic freedoms. The Kurukshetra war was fought over land dispute and Krishna’s sermon to Arjuna to fulfill his caste obligation. The message of the Gita is casteist and misogynist and as such profoundly in opposition to the spirit of modern India.’

: – The other views

There have, therefore, been many intellectuals who condemn what is presumed to be ‘the message of the Gita’.

They question: how can a spiritual being command one to wage a war knowing well the disaster that a war would bring upon the society at large and on the women and children in particular?

As regards the question of Nishkama karma (selfless action), as the scholar Easwaran writes:

the Gita’s focus is relentlessly on the doer’s attitude while he dispenses his Dharmic duty, not on what he actually does to others and its human impact. Krishna is thus able to ask Arjuna to perform ‘all actions for my sake, completely absorbed in the Self, and without expectations, fight!’

As VR Narla put it, ‘while action without seeking some personal gain can be noble, action without any care for its evil consequences to other men [is] reprehensible, even diabolical.

In The Idea of Justice, Amartya Sen too finds this problematic: ‘Krishna argues that Arjuna must do his duty, come what may, and in this case he has a duty to fight, no matter what results from it … Why should we want only to “fare forward” and not also “fare well”?

Many wonder, how could the essential teaching of the great scripture be as simple and blatant as to favor war and violence? These wise scholars sought to encourage the readers/listeners to look beyond the obvious; to delve deep; and , to un-fathom its metaphorical allegorical message.

Such bewilderment stems essentially from anxiety, dilemma and loss of direction; but not necessarily from fear or cowardice.

*

Apart from the questions of violence and war, the Gita is of much significance to the present-day world – a reflective person cannot act confidently without a thorough knowledge of the rightness of the motive and effect. Action and knowledge are very efficacious when combined with love or devotion.

[Abhinavagupta in his Bhagavadgitarth Samgraha asserts that Jana and karma are not two things.]

The Dynamic way

Whichever way you look at it, the Gita is admirably amenable to multiple interpretations. Its ‘real meaning’ (whatever be it) need not be restricted to either Jnana or Karma or Bhakti or even to violence or non-violence. The Gita could very well be read without imposing upon it one’s own interpretations. One needs: to be aware of; to recognize; and, to acknowledge its various other plausible interpretations.

Laurie L .Patton in her essay: The failure of the Allegory – Notes on Textual Violence in Bhagavad Gita ( see under section titled Beyond Allegory: Toward a Dynamic Interpretation of the Exhortation to Fight) included in the book Fighting Words: Religion, Violence, and the Interpretation of Sacred Texts edited by John Renard , speaks about a ‘dynamic way of reading ’ where one would be constantly aware of the other plausible interpretations as one chooses a particular interpretation. She concludes her very scholarly discussion on varied interpretations of the Gita with the words:

Read in this way, one can engage many possible meanings of the Gita within the clear boundaries of the verse. However, a reader would not be obsessed with the “real” meaning, nor would she be trapped by the literal meaning or the spiritual meaning, or any other possible meaning in between.

***

As Erenow questions :

What is the best way to read the Bhagavad Gita? That will of course depend on the reader. In the Gita, Krishna commends all those who share his teachings with others. Yet we see how this sharing of the Gita can take myriad forms. Just as different translators bring different backgrounds and agendas to their task of rendering Krishna’s message, so readers will themselves bring their own differing aims to the work. Among the great plurality of translations and commentaries, embodying diverse approaches to the Gita, the reader also is called on to select a path. If Krishna is correct, all those various translational paths will indeed lead the reader to him and his words.

The Bhagavad-Gita is not an abstract theological story, but is a valuable discourse through which are woven many insights, allegories and directions, which provide a broader and a meaningful vision of life. It is particularly relevant when one is placed in the very cauldron of life; facing conflicting situations; and, when one is confronted with multiple choices.

When a society enters chaos, it does not usually return to its earlier status; but, will re-invent itself; and, ushers in a new society with its own moral, cultural and social references.

In the next segment of this article, let us discus in fair detail each of the above streams of the interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita.

Continued in Part Two

References and sources

- Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita and Images of the Hindu Tradition: by Catherine A. Robinson

- The Bhagavad Gita and the West: The Esoteric Significance of the Bhagavad-Gita by Rudolf Steiner

- Exploring the Bhagavad Gitā: Philosophy, Structure, and Meaning by Ithamar Theodor

- The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students by Jeaneane D. Fowler

- Fighting Words: Religion, Violence, and the Interpretation of Sacred Texts by John Renard

- The Failure of Allegory: Notes on Textual Violence and the Bhagavad Gita by Laurie L. Patton

- A Comparative Study of the Commentaries on The Bhagavadgītā by T. G. Mainkar

- Bhagavad-Gita in Mahabharata Translated and Edited by J. A. B. van Buitenen

- My Gitaby Devdutt Pattanaik

- The Bhagavad-Gita and modern thought introduction by Shruti Kapila and Faisal Devji

- The quest for objective truth – Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita Edited by Robert Neil Minor

- Who Wrote Bhagavad-Gita by Meghnad Desai

- Da’ud ibn Tamam ibn Ibrahim al-Shawn – The Bhagavad Gita interpreted – Edited by Daud Shawni

- A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 2 by Dr. Surendranath Dasgupta

- PICTURES ARE TAKEN FROM INTERNET

[In his autobiography, Gandhi mentions that the Theosophists friends who introduced him to Arnold’s poem also introduced him to Madame Blavatsky and Mrs. Besant. He ‘politely declined’ his friends’ invitation to join the Theosophical Society, though he read, at their instance, Madame Blavatsky’s Key to Theosophy.]

[In his autobiography, Gandhi mentions that the Theosophists friends who introduced him to Arnold’s poem also introduced him to Madame Blavatsky and Mrs. Besant. He ‘politely declined’ his friends’ invitation to join the Theosophical Society, though he read, at their instance, Madame Blavatsky’s Key to Theosophy.]

Friedrich Schlege

Friedrich Schlege

Sri Aurobindo, who followed Bamkim Chandra, regarded Gita as an absolutely splendid revelation holding forth a Universal message. He advised that Gita should be approached by forgetting all the religious and academic arguments that highlight or decry one Yoga (paths) or the other. The integrated vision of the Gita, he said, transcends all such limited interpretations. He envisioned Gita as a divine action, where the battle field (Krukshetra) is in the heart and soul of every human being. Each one of us, potentially brave, fights in his or her own way with the confronting doubts, desperation, fears and frustrations. Krishna is the one, hidden behind the veils of our psyche and mind, who reveals the mysteries of life. Sri Aurobindo stressed that in the present age it was necessary to understand the Dharma, Karma and Yogas in contemporary sense.

Sri Aurobindo, who followed Bamkim Chandra, regarded Gita as an absolutely splendid revelation holding forth a Universal message. He advised that Gita should be approached by forgetting all the religious and academic arguments that highlight or decry one Yoga (paths) or the other. The integrated vision of the Gita, he said, transcends all such limited interpretations. He envisioned Gita as a divine action, where the battle field (Krukshetra) is in the heart and soul of every human being. Each one of us, potentially brave, fights in his or her own way with the confronting doubts, desperation, fears and frustrations. Krishna is the one, hidden behind the veils of our psyche and mind, who reveals the mysteries of life. Sri Aurobindo stressed that in the present age it was necessary to understand the Dharma, Karma and Yogas in contemporary sense.

On July 16, 1945, at the dawning of the atomic age, J. Robert Oppenheimer watched the first human-controlled atomic explosion at Los Alamos, New Mexico, from a bunker twenty miles away. As director of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was responsible for overseeing the creation of the bomb, which the project called “Trinity.” He was a brilliant professional physicist, and also a gifted amateur student of Sanskrit. As he observed the awesome detonation of Trinity, Oppenheimer later recalled that passages from the Bhagavad Gita sprang to his mind.

On July 16, 1945, at the dawning of the atomic age, J. Robert Oppenheimer watched the first human-controlled atomic explosion at Los Alamos, New Mexico, from a bunker twenty miles away. As director of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was responsible for overseeing the creation of the bomb, which the project called “Trinity.” He was a brilliant professional physicist, and also a gifted amateur student of Sanskrit. As he observed the awesome detonation of Trinity, Oppenheimer later recalled that passages from the Bhagavad Gita sprang to his mind.